- Home

- Delores Phillips

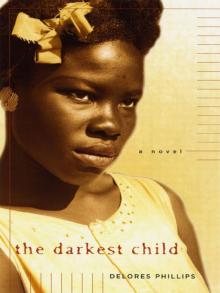

The Darkest Child Page 31

The Darkest Child Read online

Page 31

Skeeter loved to laugh and would try to make a joke of anything. I sat across from him at his kitchen table as he held Mary Ann on his lap.“Look at her,” he said.“She looks like a prune even when she’s sleeping. That’s why God gives babies a mama and daddy. Somebody gotta think they’re cute.You look at her and tell me if you see anything cute.”

“You’re lucky Martha Jean can’t hear you,” I said.

“Oh, I tell ’em all the time this a ugly baby.Watch this.”

He glanced over at Martha Jean who was washing dishes at the sink. He waited until she turned and he had her attention, then he made a face, raked his fingers across it, and pointed to Mary Ann. Martha Jean smiled, shook her head, and turned back to the sink.

“See,” Skeeter said.“She knows.Tell you what, you show me one cute thing on this little prune and I’ll let you hold her for a spell.”

I walked around the table and stood behind Skeeter to peer down at the baby.“Her nose,” I said. “It’s perfect.”

“Shoot.” Skeeter laughed.“You must be kidding.That’s Velman’s nose. Can’t even call it a nose.That’s a snout.”

“Her hair,” I said, anxious to hold my niece.

Skeeter pretended to study Mary Ann’s hair, then he looked up at me. “Okay,” he said, “I’ll give her that. She took hair after her mama.” He placed Mary Ann in my arms, then immediately rose from his chair and began to laugh. “Guess you get to change the diaper.That’ll probably be cute, too.”

“Skeeter,” I protested in mock anger.

I didn’t mind changing Mary Ann. I liked being alone with her. Her innocence was soothing to me, and I thought I would have liked to crawl inside her, to start life all over again. I took her into her parents’ room and changed her diaper, then closed my eyes and held her against my chest until she began to protest.

When I returned to the kitchen, Martha Jean was sitting at the table and Skeeter was shuffling a deck of cards.

“You wanna get in on this hand?” he asked.

“We don’t play cards,” I answered.“We don’t know how.”

“Who don’t?”

“We don’t.”

“Speak for yourself. Martha Jean plays.You want me to deal you a hand and teach you how?”

I shook my head. “No. It’s too hot to sit in a kitchen playing cards.Why don’t we go outside?”

“Who wants to go out there and have to listen to Melvin and Dot going at it like two bulldogs? I’d rather stay in here and be hot.”

The Tates had been arguing for close to an hour. By the constant changes in the level of their voices, I assumed they were taking their disagreement back and forth from the house to the yard. It was such a frequent occurrence on Motten Street that most people just ignored them.

“They the strangest two I know,” Skeeter said.“All Melvin wants to do is drink all day. I can’t understand it. He drinks anything he can get his hands on. It’s gonna kill him, too.” He held five cards in his hand and studied them, then said, “Here’s the funny thing about it. Melvin ain’t worked a job in years. Dot gives him the money to drink with, then when he gets drunk, she spends half the night and most of the next day fussing about it.The next morning she gives him money all over again.You tell me what sense that makes.”

“Maybe she wants him to drink himself to death,” I said.

“That’s what I think, too,” Skeeter agreed.“But if that’s the case, why fuss about it?”

Martha Jean placed five cards on the table and smiled at Skeeter. He looked at the cards, leaned back on his chair, and winked at her. “See,” he said. “She beats me about eight hands out of ten.”

Martha Jean went to the stove to check on her bread. Still holding Mary Ann, I went over to the back door and tried to catch a breeze. It was humid inside and out, and perspiration made my blouse stick to my back.

“Does Martha Jean ever make sandwiches?” I asked.“It’s too hot to be in a kitchen cooking.”

“Martha Jean does pretty much what she wants,” Skeeter said. “There be days when she won’t come near this kitchen. I be so glad when she do that I just come on in here and sit with her.Who you think wanna eat sandwiches?” He tapped his watch and signed, “Work.”

“I’ll walk with you,” I said, turning Mary Ann over to Martha Jean. “I’d better get on home.”

Skeeter and I were walking toward the railroad tracks when he spotted my mother’s car. I was not where I should have been, and I knew I was caught. The car rolled in our direction, and Skeeter pulled me out of the way just as the front tires hit the sidewalk.

“Get in this car, Tangy Mae!” Mama snapped.

“I thought that was you, Rozelle,” Skeeter said lightly, leaning down at her window.“You almost ran us over.”

“Go to hell, Skeeter. And get out my way.”

She was drunk. She and the entire car smelled of alcohol; it was not a pleasant ride. I found myself pressing my foot against the floor, trying to brake, as the car sped along the streets, barely missing poles, trees, and parked cars.

We had almost made it home when Mama stopped the car on the side of Fife Street. She opened her door and got out. I stared after her but turned my head when I saw that she was being sick right out in the open where people sitting on their porches could see her.

“Disgusting,” I mumbled.

She got back in the car and lit a cigarette. I would not look at her, but I heard her inhale, and I smelled the smoke as it circulated throughout the car and drifted out of my window.

“I heard what you called me, and I didn’t like it. I didn’t like it one damn bit,” she said, and attempted to press the burning tip of her cigarette against my thigh. I reached for the door handle, prepared to jump from the car. Sparks flew across the seat, and my mother swore and threw the cigarette from her window.

We made it home safely, and she parked the car in the field like a sane and sober person. She waited until we were inside before she told me why she had come looking for me.

“That damn Mr. Pace was out here today,” she said. “What’s going on between the two of y’all, Tangy Mae? He say they willing to give you pay if you go to that white school. I asked him how much he was willing to pay, but he wouldn’t tell me. So I told him you can’t go but he can see you out at Frances’s place any night he takes a notion.”

“No, Mama, you didn’t!” I cried, so mortified by her words that I did not realize I was pulling my own hair until Tarabelle reached out to stop me.

“‘No, Mama, you didn’t, ’” my mother mimicked.“Yes, hell, I did, and I think he left here mad about something.Tangy Mae, I don’t want them school people coming to my house.” She lit another cigarette. “And you get yo’self cleaned up.You gotta make a run wit’ me.”

“I’ve got the curse, Mama,” I lied.

She shifted her gaze to Tarabelle. “Tarabelle, get yo’self cleaned up.”

“I got it, too, Mama, ”Tarabelle said and glanced at me.

Mama sat with her chin resting against her chest and said nothing. Finally, her head rose and she said, “Laura Gail, you got the curse, too?”

“What curse, Mama?” I heard my sister ask.“What’s a curse?”

Tarabelle and I glanced at each other.We had known, had even predicted this moment in time. “I’ll go,” I said.

My mother laughed.“You damn right, you’ll go,” she said.“You think you smart, Tangy Mae, but you the laziest, sorriest something I ever gave birth to.”

I went out to the woods and ran the length of the path as hard and fast as I could, then I returned to the house to scrub my lazy, sorry self for a trip to the farmhouse.

fourty - seven

“She’s dead,” Wallace said. “I tried to wake her up this morning, but I couldn’t. Harvey and Mr. Dobson already know who she is. I had to tell ’em, Mama.Wouldn’t be right, Harvey taking care of his grandma and don’t know who she is.”

Miss Pearl’s hand came up to pat my mother’s back.�

��Ain’t nothing worst than being motherless,” she said.“Makes you feel like you in the world alone.”

“I always been alone, Pearl,” Mama said. “Ain’t nothing new ’bout that.”

Any sadness I might have felt was overshadowed by disappointment. It was as though I had been reading a really great novel when suddenly, right at the climax, I found an entire chapter missing. Now I might never know that significant something that had taken place between the beginning and the ending.

“You can come on home now, Wallace. Ain’t nothing to hold you on Selman Street, and I don’t want you at the funeral.The less people know, the better,” Mama said.

“I gotta go to the funeral, ”Wallace said, “and I don’t wanna come back out here. Somebody gotta take care of Mr. Grodin.”

“I can’t believe this,” Tarabelle said. “Mama, how come you didn’t tell us that ol’ woman was kin to us?”

“You didn’t need to know,” Mama told her. “Nobody woulda knew if Wallace hadn’t got too big for his britches.”

“I’m going to the funeral, too, ”Tarabelle announced.

“You didn’t even know her.Why you wanna go?” Mama asked.

“Just ’cause I can, and you can’t stop me. Today is August twenty-eighth, and I’m eighteen. I’m grown.”

Mama began to laugh. She stomped her feet against the floor and clapped her hands. It was so bizarre that Miss Pearl’s hand ceased its ineffectual consolation and flew to her mouth.

All Tarabelle had to do was pack her things and leave, but she did not do that. She walked across the hall and entered our mother’s room, and the sound of scratching, like a big tomcat clawing on planks, reached us in the front room.

Mama sprang from her chair and rushed toward the room. “What you doing?” she yelled.“Get outta here! This is my room.”

I had followed my mother. I saw my sister prying up the floorboards with her bare hands.

“I wanna know what’s in that box, Mama,” Tarabelle said. “Before I leave here today, I’m gon’ know what’s in that box. What’s so important that you woulda killed us all for?”

“Give it to me!” Mama shrieked, and reached for the box that was still attached, by nails, to the floorboard. It was weathered and discolored, but it was the same box that she had put under the house all those years ago.

Tarabelle managed to pry the box from the board and struggled to free the sliding plate. Mama rushed toward her, and as she did, the plate slipped free. Locks of hair, tied together by moldy, withered ribbons, spilled out onto the floor.

“Hair!”Tarabelle cried.“You woulda killed us for hair, you crazy bitch?”

Mama leapt into the air, mindless of the rusted nails that jutted out from the boards. She landed a foot squarely at the center of Tarabelle’s back. Tarabelle jerked forward from the blow, but quickly sprang back, turned, and swung a board at Mama’s legs. Mama was out of reach.Then, as the board swished past her knees, she moved in determinedly, gripped Tarabelle’s hair with both hands, and stepped behind my sister.Tarabelle dropped the board. Her head snapped back and her eyelids fluttered rapidly. Mama untangled one hand from Tarabelle’s hair, made a fist, and brought it down with all her strength.Tarabelle’s nose seemed to explode, and blood flew everywhere.

Tarabelle was temporarily dazed, but recovered quickly. She twisted her body around and clawed at Mama’s arms. She swung a fist at Mama’s abdomen that connected but did no damage. She steadily clawed and punched until she brought our mother down with her. Mama, with one hand still entangled in Tarabelle’s hair, hit the floor sideways, right over the opening created by the missing boards.Tarabelle’s head was yanked forward with what seemed enough force to snap her neck. Fighting for survival, she opened her mouth and sank her teeth into the flesh of Mama’s calf. The blood from Tarabelle’s nose covered them both.

Mama let go of Tarabelle’s hair. She screamed, bucked and kicked, but could not loose herself from Tarabelle’s teeth.With her free hand, she reached behind her back and made feeble attempts to strike.

Wallace and I moved forward to separate them. I coaxed and tugged at Tarabelle while Wallace restrained Mama’s hand. I managed to get Tarabelle out of the room, and there was Miss Pearl, standing in the hallway, peeling red crepe paper from white socks. She removed one sock from the pair and pressed it against my sister’s bleeding nose.

Wallace was breathless when he stepped from Mama’s room, but Miss Pearl did not give him a chance to catch his breath. “Take Tarabelle out to the yard,” she said.“See if you can’t get that bleeding stopped.”

Wallace looked at me. “I ain’t never coming back, Tan,” he said, his chest heaving.

“Eventually, she’ll come and get you,” I told him.

“She can’t,” he said, staring at me oddly, as if to say, Tan, I’ve got another secret.

Miss Zadie was buried on the first Thursday in September when the county fair was in town, the weather was still pleasantly warm and the sky was a clear blue. It did not seen a proper time for death.

Laura, Edna, and I were cloaked in heavy mourning, and it had nothing to do with a grandmother we had never known as such. I think we were mourning the loss of stability. The departure of Wallace and Tarabelle brought a bleak finality to all that remained of our family.

Mama crawled from her bed on that Thursday, went out for a short while, and returned to sit in her favorite spot on the front porch. She unscrewed the lid from a Mason jar and began to drink. Fresh abrasions on her face indicated that her bugs had returned, and I think she was trying to poison them with the spirits she gulped from the jar.

Miss Pearl was the only person who came to our house after the funeral. She sat on the porch with Mama and asked for a drink of water. I placed the last of our ice in a jar and dipped water over it, then took it out to her.

“Thanks,” she said, reaching for the jar.“That was a nice service they had for Miss Zadie. Nearly everybody in town showed up. She was well liked.”

“They didn’t know her, ”Mama said bitterly.“Was Tarabelle there?”

“Sho’was. Harvey, Wallace, and Tarabelle. Folks was just shocked that you didn’t come, Rosie.They got yo’ name wrote here on this paper.” Miss Pearl reached into her pocketbook and withdrew a folded sheet of paper. “Folks couldn’t believe it.They kept asking me, and I just went on and tol’ ’em the truth.Ain’t no need to hide it now when it’s wrote on this here paper for the world to see. Got all yo’ chilluns listed here, too.”

Mama wept softly.“Who went and done that?” she asked.“That ol’ woman dead now.Why folks gotta know ’bout me?”

“I reckon the ol’ man done it,” Miss Pearl answered, setting her jar on the porch floor, and leaning over to pat Mama’s back.“Ain’t no need to cry ’bout it, Rosie. She was yo’ mama plain and simple. Ain’t no denying that.”

“She was a liar,” Mama said.“Everything she ever tol’ me was a lie.That hair that Tarabelle went and spoiled—that ol’ woman tol’ me I could hold folks wit’ that hair. It was just a lie, Pearl. All my babies gone. Everybody I ever loved is gone.”

Miss Pearl dropped her hand from Mama’s back, and picked up the Mason jar.“Here, Rosie.You take another sip of this and calm yo’ nerves.We been friends a long time and I ain’t never knowed nobody you loved enough to make you carry on like this.”

Mama drained the last of the corn whiskey from her jar, placed the jar on the floor, then turned toward Miss Pearl. “You think I didn’t love Sam, Pearl? He wadn’t no more than two when I cut his hair, and where is he now? It wadn’t s’pose to be like this. All my babies s’pose to be here wit’ me—not scattered all over the place. I can’t even get Wallace to come home, and do you know why, Pearl? It’s ’cause that ol’ woman peed in a bottle and tol’ him to sprinkle it on me if I come near him.”

She screamed then, so loud that I jerked back and fell against the door frame.

“Ol’ dead woman piss in a bottle,” she sobbed. “It’ll burn

holes in yo’ skin, Pearl. It’ll make warts grow on yo’ face, and that damn Wallace was gon’ put it on me. I’m his mother, and he was gon’ throw it on me.That hair don’t mean shit. All them years, and you seen what happened.You seen Wallace try to fight me.”

Miss Pearl gently rubbed Mama’s arm. “He wadn’t trying to fight you, Rosie. He was trying to help you.”

“Who ever tried to help me?” Mama asked, slapping one palm against her chest.“Nobody but you, Pearl.You the only somebody I got in this world. I ain’t had no mother.That woman—she dead, but y’all don’t know what she was like. She took my hair. I seen her put it in a box, and she said I wouldn’t never be able to leave. She was right, too. I can’t get outta here. Every time I try, something pulls me back. It’s a spell, but it don’t work for me.Everybody leaving me and I can’t go nowhere ’cause I don’t know how to work that spell.”

She leaned forward, as if the pain was too much to bear. I found myself moving toward her. I extended a hand and touched her heaving shoulder, then I brought her head to rest against my abdomen.

“Don’t cry, Mama,” I pleaded. “Please don’t cry. I love you, and I won’t leave you.You can have my hair, but please don’t cry.”

Laura came to stand beside me. She placed her hands on Mama’s knees.“Mine, too, Mama,” she said.“You can have my hair.”

“It won’t work,” Mama sobbed.“All the hair in the world won’t work when she didn’t tell me how to do it right. She never tol’ me nothing. I’m glad she’s dead.”

Miss Pearl pulled a handkerchief from her pocketbook and dabbed at her eyes.“You ain’t glad, Rosie,” she said.“You just hurting the way you s’pose to when you lose a mother. It’s a sad thing.”

Mama leaned heavily against my abdomen and wrapped her arms around my waist. She began to cry harder, and I believed she was grieving for her mother. I knew I felt something for mine. She held onto me until her tears had subsided, then she reached down for the Mason jar and brought it to her lips. It was empty, and she threw it over the side of the porch where it landed and broke in the gully.

The Darkest Child

The Darkest Child