- Home

- Delores Phillips

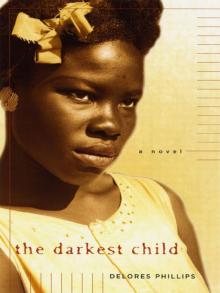

The Darkest Child Page 9

The Darkest Child Read online

Page 9

We laughed.

Mama laughed, too. “Pearl, you know you a mess,” she said. “Don’t you shake my house down.”

“Well?” Miss Pearl asked.“You coming or not? I got Frank waiting out in the car.”

Mama massaged her abdomen through the pink housedress, and her tongue circled her colorless lips as she contemplated the invitation. Finally, she said, “I don’t know, Pearl. Mushy just got here. She done come all this way to see me.”

“Oh, shit, Rosie!” Miss Pearl exclaimed. “I ain’t talking ’bout keeping you all week. Ain’t gon’ hurt nobody for you to get out for a bit. C’mon, girl.”

“Okay. Just let me change my dress and put on a little lipstick,” Mama said, and rushed across the hall.

Miss Pearl leaned toward Mushy, and whispered, “I’m gon’ do the best I can, but I don’t wanna get in no trouble wit’ yo’ mama. And who gon’ be keeping a eye on this baby while y’all up there running wil’?”

“We already got that figured out,” Mushy lied.

“Humph,” Miss Pearl grunted.“You better have it figured out.” She stepped away from Mushy, and as she did, her foot bumped a bowl of rainwater, spilling it onto her foot.“Goddamn!”she shouted, looking down at her feet. “Harvey, y’all need to do something ’bout that roof. Next clear day, y’all need to climb up there and fix that thang.”

Standing against the wall behind the stove, Sam grinned.“It ain’t our roof, Miss Pearl.This house belong to Mr. Poppy.”

“Well, he ain’t gon’ fix it,” she said.“That white man don’t care if y’all drown in here. Can’t you see that? He’ll just rinse y’all out and rent to the next po’ niggers come along.”

“I heard that, Pearl,” Mama yelled from her room. “The one thang we ain’t is po’, and the one thang we ain’t never gon’ be is niggers.”

“Shit,” Miss Pearl said, rolling her eyes toward the ceiling. “C’mon, girl. Frank out there waiting on us.”

As soon as they were out the door, Mushy seemed to be everywhere at once. She opened her suitcase and removed several items of clothing, she stuck the flat iron on top of a stove eye, she examined my hair and pulled a comb through it several times, then she reached into her purse and withdrew two dollars. “Wallace, I’m gon’ give you these two dollars to watch Judy and the girls,” she said.“You think you can do that?”

“How come I can’t go?” he asked, eyeing the bills, but not reaching for them.

“You ain’t going, Wallace, so don’t mention it no mo’,” Harvey said.

“I’ll watch ’em, ”Tarabelle said.“I can’t go wit’ y’all to Stillwaters no way.”

“What you mean you can’t go?” Mushy asked incredulously. “All day we been planning this, and now you say you can’t go.You ain’t gotta worry ’bout Mama. Miss Pearl gon’ keep her up to her place ’til we get back.”

“I ain’t worried ’bout Mama. I just can’t go up to that place.”

She spoke with such loathing that it momentarily squashed my enthusiasm, but Stillwaters was a place for adults, and I wanted desperately to feel grown, if only for one night. I intended to stroll into the place feeling special and looking pretty in the nylon stockings and red sweater Mushy was allowing me to wear. I would be with Mushy, and nothing bad ever happened when she was around.

We were ready and waiting when our ride pulled up. I tipped through the muddy yard and down the bank to the car, trying to keep my shoes clean and the rain from kinking my hair again.

“Y’all remember Hambone?” Sam asked, after we were settled in the car.

The young man turned on his seat and greeted us with a nod. I returned his nod, then sat back and stared up at our house where the kerosene lamp exposed paper-covered windows, barely visible through the rain and darkness. For a moment the guilt of disobedience washed over me, then the car began moving, bearing me away from Penyon Road, and I made myself relax.

fourteen

Stillwaters Café was a long, wooden, T-shaped structure, ten minutes up the four-lane highway and five minutes down a narrow, dirt road that turned left onto a graveled drive. It stood at the far edge of a clearing, flanked by tall pine trees.

Hambone, showing expertise in maneuvering the car, had brought us here safely, pulling to the edge several times to allow other cars to pass, not once landing us in one of the wide ditches that saddled the road. He pulled into the lot and parked between two dark-colored pickup trucks.

Loud music drew us inside. Left of the entrance was a dim yellow light, illuminating a pool table, a jukebox, and a short, circular bar that enclosed a cooking area.To the right, under a red light, was a scattering of tables and chairs, and against the back wall, a platform where a band entertained the crowd with a rendition of “The Great Pretender.” Deeper into the darkness, under a blue light, was a dance floor where several couples slowly swayed.

Mushy scanned the hall and waited for the music and applause to end, then she called out to a man behind the bar, “Fox.” Once again in a louder voice, “Fox!”

A powerful-looking man, who could have been about fifty, craned forward trying to locate her voice.“Mushy?” he shouted in surprise.

Mushy shimmied out of her coat, revealing a skintight, V-neck, sleeveless black dress with tiny black bows stitched in at the hips. “It’s me,” she said, spinning around, “yo’ Georgia peach back in Dixie, packaged and handled wit’ care just for you, Fox.”

“My God, girl,” Fox grinned, stepping from behind the bar, a dirty white apron bunched around his waist. “Mushy, girl, you looking good.” He embraced her in a hug that seemed to swallow her up, and she returned his hug and stepped away smiling.

“Don’t you get that chit’lin’ fat all over my dress,” she teased.

“Nah, nah,” Fox said.“We ain’t having no chit’lins tonight.What you want, girl? I’ll go back there and get you anything you want.”

“Let’s see,” she said, pretending to think about it.“I want a ocean of gin, Fox.That’s what my belly’s calling for.”

“Be right out, Mushy. Don’t you go nowhere.”

We settled at a table near the bandstand just as the band began to play a Chuck Berry tune. A few couples moved out onto the dance floor, and I watched them as my feet tapped the wooden floor beneath the table.

“You wanna dance?” Hambone asked, and I nodded. He was short, only an inch or two taller than I. He had a dark brown complexion, a square, hairless chin, and a flat nose. His appearance, I noticed, had not changed that much during his absence from Pakersfield. He, and his voice, were heavier, and that was all.

We danced, and when the song ended, he leaned toward me and said, matter-of-factly, “You’re the smart one Sam is always talking about.”

It pleased and surprised me that Sam had spoken of me to his friend. I smiled foolishly, not knowing how else to respond.When we were back at our table, Hambone sat next to me and stared until I began to feel uncomfortable. Fox had set our table up with bottles and glasses, and I toyed with an unopened bottle of beer.

“Tell me,” Hambone said finally, “how does it feel to be smart and pretty at the same time? That must be an awful lot for a little girl like you to handle.”

“I do all right,” I answered, blushing.

Harvey, beer in hand, wandered off toward the pool table, and Mushy restlessly shifted on her seat, searching the room for familiar faces. Sam poured drinks from a gin bottle for everybody at the table, except me and Martha Jean.

Hambone swallowed the liquid in his glass and followed it by draining a bottle of Black Label beer. “You remember me?” he asked.“Your brother ever tell you anything about me?”

“I’ve heard him mention you.”

“I know it was something good.You know, Sam is all right. He knows how to think.” Hambone jabbed a finger at his head.“I like to be around smart people—people who can think.”

I groaned inwardly, then reached out and swiped an open bottle of beer from the table. I

t was my first attempt at being an adult, and I wanted to have fun, not talk about being smart.

The band counted off for another tune, and a man appeared at our table to ask Martha Jean to dance. He stood there with a hand extended, and Martha Jean glanced at Mushy. Mushy pointed to the dance floor and moved two fingers swiftly about in circles. Martha Jean rose, took the man’s hand, and followed him to the dance floor.

I nearly choked on the beer I had swallowed.“Mushy, she can’t even hear the music,” I shouted across the table when I was able to speak.

Mushy waved a hand in dismissal.“Let her dance, dance, dance,” she said, raising her arm higher with each word. “She can feel the vibrations. She’s done it before, Tan. You know that. She’ll be awright.”

“At Miss Pearl’s house,” I said, “but never in public.”

Mushy paid me no attention. She moved out to the dance floor, leaving me staring after her, and I hadn’t even seen who’d asked her to dance.

“Guess I’d better find me a partner,” Sam said, pushing his chair back, and I was left sitting alone with a man who wanted to talk to me about being smart.

“You ever drink beer before?” Hambone asked, lifting a bottle and pouring the contents into a glass.

“No.”

“I didn’t think so.You let it set too long and it goes flat on you.

Nothing taste worse than flat beer.”

“Is that so?” I asked in an uninterested tone.

“You don’t have no business in here drinking beer anyway,” he said.“How old are you?”

It was a question he should have asked before he drove me to Stillwaters, so I did not bother to answer. I reached across the table, seized Mushy’s glass and swallowed down a piney-tasting beverage, then fought the urge to retch.

Hambone watched with amusement. “Not what you thought, huh?”

I turned the glass up and swallowed down more just to shut him up, and to quench the burning sensation in the back of my throat.

“I’ve been wanting to ask a smart person about Pakersfield,” Hambone said.“What do you think about this town?”

“I like it.”

“Well, yeah, I know you like it.You don’t have anything to compare it to, but that’s not what I mean.What do you think about the way these white people treat you?”

“Mostly, they treat me all right.”

“How’s that?”

“Well, they give us a school. They supply our library with books, and they give us vaccinations in their library.”

“Yeah, they do,” Hambone agreed. “In the basement of their library. I remember that.You ever wonder why they give Negroes shots in the basement of a library?”

“It doesn’t matter.We get the shots free, and that’s what counts.”

“You’re not smart,” he said coldly.“You’re pretty, but don’t ever let anybody tell you that you’re smart again. You think they’re doing so much for you? Why don’t you try reading one of them damn books in that library, see how far you get.”

He was right. I stared down at the table and could think of no response.

He touched my chin with a curved finger, and said, “Don’t look so sad. It’s all about what you can and can’t do.Take your brother, Sam. Junior got him thinking he can make some changes by drinking from a damn water fountain.”

“When?” I asked.

Hambone shrugged.“Sometime soon.”

“Will you be with him?”

He stared at me, then said, “Probably. But if I’m gon’ get my head busted, I want it to be over something more important than a drink of water. It ain’t gon’ work no way. The ones in positions to help them out, like the reverend and Mr.Hewitt, are too scared of these white people to lift a finger.That’s where we have to start. We’ve got to bring the young and old together.”

I was nodding my agreement when the music ended and Mushy returned to the table.“Did you see Martha Jean?” she asked breathlessly.“ That’s Walt Jones she dancing wit’.You remember him, Tan? Look at ’im standing over there trying to talk to her.”

“Mushy!” I cried, springing to my feet and experiencing a wave of light-headedness.“You left her out there?”

“Sit down, Tan,” Mushy said.“We out to have a good time. Let Martha Jean do whatever the hell she wanna do. It ain’t gon’ hurt nobody.”

I did not make a fool of myself by charging the dance floor as I had intended, but I did not sit down, either, not until I saw Martha Jean emerging from the blue light into the red.

“Where’s my drink?” Mushy asked, eyeing the empty space on the table in front of her, then the glass in front of me. “Girl, you done sit here and drunk my drink?” She laughed. “Tangy Mae, I don’t wanna have to carry you outta here.”

The band had fallen silent and they were now packing up their gear. Mushy turned on her seat and faced the platform, then she poured herself a drink, stood, and held her glass up toward the band.

“Hey, where y’all going?” she called out.“I ain’t heard no blues yet.”

One of the band members, a chubby man who had done most of the singing, stepped to the edge of the platform and stared out at Mushy.“You got the blues, little mama?” he asked with a wink.

“I sho ’nuff got the blues, big daddy,” Mushy answered, swaggering toward the platform.

“Your sister is something else,” Hambone said, shaking his head in what I thought was disapproval.

Mushy stepped up onto the platform, and the band members unpacked their instruments and repositioned themselves. Mushy smiled down at the expectant crowd.“Y’all waiting on me to sang?” she asked, and a cheer of affirmatives rolled through the three degrees of darkness.“Well, I can’t sang.” She took a sip from her glass and held the glass up as if she were toasting the world.“I never could, but I got a sister out there can sang her little ass off. Come sang for these people, Tan.”

Mushy was drunk or pretty close to it. For a moment I shared Hambone’s sentiment, then I stood, tugged my black skirt up an inch, pulled the red sweater down over the rolled band of the skirt, and straightened, as best I could, my on-loan, sagging nylons.

“Sang ‘God Bless the Child, ’Tan,” Mushy urged as she stepped down from the platform and I stepped up. “Sang it, Tan, ’cause I need God to bless me.”

As the music began, I felt a warmth spread through me and I stared out at faces I could barely see, then I opened my mouth.My two dynamic voices fused. I sang with my own strong voice—the voice that made people shout at the Solid Rock Baptist Church, and I sang with the voice Martha Jean had left in our mother’s womb—the voice I had stolen. I harmonized those voices perfectly, and I crooned for the love of my sister, “God bless the child that’s got his own.”

When the song ended, there was silence in the hall. I could see the people again, staring out and up at me. Sam stood just below the platform, and behind him was Harvey. I had done something to these people, but I wasn’t sure what until Mushy raised an empty glass and said, “Didn’t I tell y’all?”

The applause was thunderous.The chubby band member winked at me and asked if I would like to sing another song. I shook my head and floated back to my seat on a cloud of sinful pride as people praised my talent. I refused to feel guilty or afraid, even though I knew that I had brought attention to myself, and someone in the hall would probably tell my mother what I had done.

“Okay,” Hambone said, after I was seated.“You’re pretty and you can sing, but you’re still not as smart as I thought.”

“What you mean by that, Hambone?” Sam questioned.“Tangy Mae ’bout the smartest person at Plymouth school.”

I knew what he meant, but the others waited for him to answer. Before he could get his first word out, though, Martha Jean leapt to her feet, knocking over two glasses, and startling us all.A voice from behind me said, “That was some real good singing, little sister.”

I turned to see Velman Cooper. His processed waves had been replaced by a neat hairc

ut. He was wearing blue jeans, and a sweater that appeared deep purple under the red light. Shamelessly, Martha Jean strode up to him and gripped his hand in her own.

“Hey, wait a minute, man!” Sam barked, as Velman leaned over and kissed Martha Jean fully on her lips.“Who the hell . . . ?”

“That’s Velman Cooper,” I answered. “He works down at the post office.”

“And why is he all over Martha Jean?” Sam demanded. I shrugged my shoulders.

“Take yo’ lips off that girl and grab a seat,” Mushy said lightly. “Last thang we need is you and Sam tearing the place up, and knocking over all the liquor.You start whupping Sam, Harvey’ll have to jump in. And Lord have mercy if you start beating ’em both. I’d have to jump in, and as you can see I ain’t in no shape to fight nobody tonight. So please, just sit down—right here next to me.”

Velman pulled a chair from another table and placed it between Mushy and Martha Jean. Sam scowled at him, while Harvey watched with quiet amusement.

“So you work at the post office?” Hambone asked.

“That’s Hambone,” I said in response to Velman’s questioning gaze, then I made introductions around the table.

“Andrew Freeman,” Hambone said, giving his birth name and extending a hand across the table.“I’m interested in smart people. You must be pretty smart if they let you work at the post office?”

“Smart enough, I guess,” Velman answered.

“Let me ask you, and this smart one over here,” Hambone gestured in my direction, “what you would do if you worked all day for one of these rednecks in this town and they refused to pay you?”

“That depends,” I said.

“On what?”

“On why they didn’t pay me.”

“Okay. They didn’t pay you because they didn’t want to, and because they don’t have to.What would you do?”

“I wouldn’t work for them again,” I said. “I’d find myself another job.”

“But you already worked,” Hambone said bitterly.“You already earned the money that you didn’t get. Don’t you understand what I’m saying here?”

The Darkest Child

The Darkest Child