- Home

- Delores Phillips

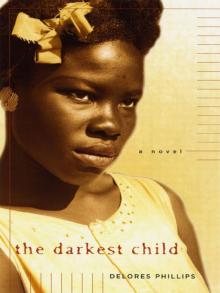

The Darkest Child Page 11

The Darkest Child Read online

Page 11

Our mother stood at that rickety, old table, kneading guilt that she would later bake and feed to us in bite-size pieces. And I was determined to swallow mine without gagging or choking, although guilt has a stringy texture, like strands of hair in a bowl of Cream of Wheat.

“What the Bible say, Mushy?” Mama asked.

Mushy inhaled deeply and exhaled slowly.“Honor thy mother, Mama.”

“Do you honor me?”

“Where the Bible, Mama? I ain’t never seen no Bible in this house.”

“Do you honor me?”

“Where’s the Bible?”

“I’m yo’ mother. I gave you life. Now, I ask you again, do you honor me?”

Mushy shook her head slowly, as if in resignation. Her chest heaved and her jaw tightened. Finally she deflated with a soft sigh and a bitter laugh.“Yes, ma’am,” she said, and strode from the room with her eyes downcast.

Later, Sam and I found her sitting outside on a step, shivering, humming an old blues tune, and clutching an empty Mason jar.

Our somber mood seemed to bring out the gaiety in our mother. She washed the flour from her skin, brushed her hair, and changed into her new blouse, a plaid skirt, and high-heeled shoes, then she herded us along the dark, muddy roads to the Garrisons’ house.We did not want to go, but we were given no choice.

There was a light on at the back of the Garrisons’ house, and Squat, Mr. Frank’s old sooner, stood in the backyard and stared out at us through a wire fence. He did not bark, probably because we were as familiar to him as the scraggly patches of grass covering his terrain.

Mama, seemingly contented with the world, sauntered over to the fence. She knelt down and poked a finger through an opening. “Hey, boy,” she cooed, “you lonely back here all by yo’self?”

Squat took a step back, cocked his head to the side, and watched Mama’s finger waggle inside the opening.

“No wonder you lonely,” Mama said. “You ain’t friendly enough. Come here, boy. Come here.” She tapped a hand against her thigh and snapped her fingers, only to have Squat turn tail and lope across the yard.

“You lucky he didn’t take that finger off,” Mr. Frank said, opening the screen door and stepping out onto the porch.“Squat don’t like cats, Rozelle, especially alley cats.”

“What you mean by that, Mr. Frank?” Sam asked. “That’s my mama you talking to.”

Mr. Frank stared down at Sam, saw his clenched fist and heard the anger in his voice. He had no way of knowing that Sam’s irritation stemmed more from swallowing guilt and being forced out into the cold, wet weather than from anything he had said.

“Just joking wit’ her, son, ”Mr. Frank said, probably remembering, as I was, how Sam had opened Chester Riley’s skull with an axe handle over a derogatory remark made about Mama.He would never do that to Mr. Frank—I hoped.

“Watch yo’ manners, Sam,” Mama said, stepping away from the fence and toward the porch. She placed a hand on the rail and tilted her head up to face Mr. Frank. Her back was to me and I could not see her expression, but something she did caused Mr. Frank’s eyes to soften momentarily. He stared down at her, then chuckled softly.

“You know what I want, Frank,” she said, “but you just like that ol’ dog of yours.You oughta try to be mo’ friendly.Where’s Pearl?”

“In the house resting up for work tomorrow. Something you don’t know nothing about.”

“I work,” Mama said lightly. “You just done forgot how hard I work.You so busy trying to be mean that you done forgot.”

The muscles in his face twitched. His bushy eyebrows and mustache seemed to target then surround his short, thick nose as his eyes narrowed and grew dark under the shadows of his brows. He turned away from Mama, stepped down from the porch, and marched across the yard to stoop beside Squat.

“Nah, you don’t like cats, do you boy?” he said, placing a hand on Squat’s head.

Mama was smiling when she turned to face us.“My babies,” she said. “My beautiful babies.” She hugged Sam, then took Edna by the hand. As she led us around to the front of the house, I stared down at her heels and saw them break the mud with each step she took. I could never have walked so far on wet earth in high-heeled shoes. I would never have tried. That was one of the differences between me and my mother.

Miss Pearl was sitting in the living room on three-fourths of her sofa. Her feet were propped on a footstool, and she stared at a small television screen. “Hey, y’all leave that mud out there!” she shouted, after Mama had pushed the door open.We removed our shoes. Mama did not.

“Pearl, do you know yo’ husband sitting out there in the mud wit’ that ol’ dog of his?” Mama asked.“I’m gon’ yell out the kitchen door and tell ’im to come on in here wit’ the rest of us.”

We parted our huddle and allowed her to saunter by, her heels clicking across the hardwood floor, and her hips swaying.We could hear her opening the back door and calling to Mr. Frank.

Sam, his anger abated, apologized.“I’m sorry, Miss Pearl. I don’t know what’s wrong wit’ Mama.We knew it was too late to be coming out here, but she wouldn’t hear nothing we had to say. Made us all come.”

“Hush, boy.” Miss Pearl waved a hand to silence him.“You ain’t gotta explain nothing to me. I been knowing Rosie since befo’ you was born. I know how she is.”

“I wish you’d tell me, ”Tarabelle said. “I don’t ever know what Mama gon’ do. I’m so sick of her, Miss Pearl, I could just scream.”

“Now, girl, you watch what you saying,” Miss Pearl warned.

“I know what I’m saying, ”Tarabelle snapped. “I’m sick of her. We all sick of her. She won’t touch Judy. I ain’t never seen a mother won’t touch her own child.”

“Maybe that’s ’cause y’all don’t give her a chance,” Miss Pearl said, getting to her feet. She went out to her kitchen and left us to stare at each other and ponder her remark.

I lowered myself to the footstool and changed Judy’s diaper, then I turned her on my lap where her head was resting against my knees so that I could gaze at her face. Sometimes I would gently squeeze the tip of her nose, trying to shape a point out of flatness. Miss Pearl had said that a baby’s head and nose could be shaped if it was done early enough, before the bones formed. She had also said that the color of the baby’s ears determined the color of the child. Judy was going to be black, maybe even a darker shade of black than I was.

“I got a big pot of pinto beans in here,” Miss Pearl called out to us. “Y’all welcome if you want some.”

We did not.

When she came back into the room, she was followed by Mama and Mr. Frank. She had a red package tucked beneath her arm, and a bowl of beans in her hand. She stood over me for a minute, looking down over my shoulder at Judy.

“Y’all hold that baby too much,” she said, her mouth filled with beans. “After while y’all ain’t gon’ be able to put her down. I like babies, but you ruin ’em if you hold ’em too much.”

“I try to tell ’em, Pearl,” Mama agreed, “but you can’t tell ’em nothing.They think that child a doll.”

“She is a doll,” Mushy said. She was sitting on the floor beside the coffee table, sweating corn whiskey and looking thoroughly miserable.

“You awright, Mushy?” Miss Pearl asked, reclaiming her seat on the sofa and handing the red package to me.

“I’m fine, Miss Pearl,” Mushy answered, attempting to hold her head up and to smile, and failing at both attempts.

“It’s the weather,” Miss Pearl said. “It’s done rained just about every day since you got here.You gotta eat if you gon’ stay healthy in this weather. Here.” She dipped her spoon into the bowl of beans and offered it to Mushy.“Beans warm you up from the inside out.This just what you need.”

Mushy closed her eyes, then tried to get to her feet.“Open the door, Wallace,” she managed to say before bumping the table and crawling for the front door.

“Um huh.”Mama nodded her head.“That�

�s what happen when they think they grown.”

“Good Lord!” Miss Pearl exclaimed. She leaned forward, her spoon poised in the air, as she watched Mushy crawl through the doorway.“What’s wrong wit’ her, Rosie?”

“Ask Harvey.”

Harvey, who had been keeping his distance from Mama all evening, leaned his head toward Mr. Frank’s chair. He was sitting on the floor with his knees up and his hands cupped over them. He tried to speak, stammering over one word and slurring the next, “We . . . we . . . I, it was just . . .Mama, it was just . . .”

Miss Pearl dropped her spoon into the bowl and shoved the bowl toward Laura. “She’s drunk?” Miss Pearl asked. “Rosie, we gon’ have to give her some cast’oil and turpentine.Work that poison out befo’ she get back on the train.”

Mama chuckled.“Pearl, Mushy ain’t no child. She probably got half it out already.” Mama kicked off her shoes.“Tarabelle, go out there and make sho’ Mushy awright,” she said as she picked up one of the shoes.

Harvey’s debilitated reflexes held him immobile as the shoe flipped, heel over toe, the distance of the room. Drunken sobs of relief escaped him as the shoe sailed past its target and struck Sam, who was sitting against the wall behind Harvey. Sam touched his fingers to his head.

“Stupid!” Mama accused. “Sam, you mean to tell me you ain’t got sense enough to move when something flying at yo’ head? I shoulda threw the damn thing at you.”

“Rozelle, you gon’ hurt one of these children one day, you keeping acting like that,” Mr. Frank admonished. “And don’t be throwing stuff in my house.You coulda hit that baby.”

“Tangy Mae, go on and open yo’ present,” Mama said, ignoring Mr. Frank.

I handed Judy to Martha Jean, and ripped the red paper from my gift.

“How you like ’em?” Miss Pearl asked.

Every year, for birthdays and Christmas, Miss Pearl gave us the same thing—a pair of white socks wrapped in red crepe paper— and we always appreciated them. I had a suspicion that someone on Meadow Hill gave them to her, and she held on to them for these special occasions.

“I like them,” I answered, as I did every time she asked that question.

“Like what?” Mushy asked. She stepped through the doorway looking disheveled, but walking upright. She took a seat on the arm of the sofa while I held my socks up in answer to her question.

“That’s the one thing we could always count on, Miss Pearl,” Mushy said affectionately. “No matter what the day was like, we always knew you’d have us a present. I miss that.”

Miss Pearl reached out and touched Mushy’s hand. “You awright, girl?” she asked.“I thought we was gon’ have to give you cast’oil.”

“Come on now, Miss Pearl,” Mushy said, glancing over at Mama. “I’m my mama’s child. If I can’t hold a little liquor, I ain’t got no business calling myself a Quinn.”

“What’s that s’pose to mean?” Mama asked.

“Means you a good teacher, Mama,” Tarabelle said from her stance in front of the door.

Up came the other shoe but too slowly to catch Tarabelle as she side-stepped. It smacked the door, then fell to the floor with a light thump. Harvey belched something resembling a laugh, and Laura giggled. Mama eased to the edge of her seat. She was preparing to strike but in which direction I could not tell.

“Mama,” Mushy said, moving over to kneel beside our mother’s chair, “when I was outside, I was thinking ’bout that winter when everything froze up.You remember? We couldn’t get down the steps ’cause they was covered wit’ ice.”

“Get away from me, Mushy,” Mama snapped, then she turned toward me, but spoke to Miss Pearl.“Pearl, did you know our quiet, little birthday girl can sang. I hear she sangs the blues like an angel.” Her voice became harsh. “Stand up and sang for us, Tangy Mae!”

“Cut it out, Rozelle,” Mr. Frank pleaded, but Mama ignored him again.

“Tangy Mae, I hear you sang right pretty for a bottle of gin. Is that right? Did you go out and shame me for a bottle of gin?” Her head appeared disembodied, floating toward me until I could see the dark circular outline of her throat. “Get yo’ black ass up and sang. Now!” she barked.

I stood, my mouth so dry I could not swallow the lump in my throat that was threatening to choke me. I opened my mouth and began to sing the first song that came to mind. It was a Clovers’ tune that I butchered unmercifully, but Mama had no shoe left to throw and I was safe for the moment.

When I finished, Miss Pearl was the only one in the room looking at me. “Y’all shoulda tol’ me if y’all wanted to hear some music,” she said. “We coulda put on some records ’cause that sho’ ain’t how that song s’pose to go.”

sixteen

“It’s a shame,” Mama said, as she stood in the doorway and watched Richard Mackey drive off with Mushy.“That boy got a wife. Ain’t no telling what people gon’ say.”

I couldn’t see how it mattered since Mushy would be on her way back to Cleveland by this time tomorrow. But I respectfully listened to my mother rant, finished my homework, then stretched out on my pallet and fell asleep feeling depressed and already missing my sister.

At some time during the night, rain fell from the sky and awakened me with a constant and annoying drip against my face. I sat upright and heard a muffled giggle from the center of the room. “Mushy?” I questioned.

“It’s me, Tan,” she answered. “I was just sitting here wondering who was gon’ wake up first. I had my money on Edna.That rain’s giving her a bath over there, and she sleeping right through it.”

I couldn’t see Edna or Mushy, but I stretched my arm over to where I knew Edna slept, and felt rain splash against my wrist in heavy drops.“What time is it?” I asked.

“It ain’t no time, Tan. It’s just almost time,” Mushy answered.

“You ever notice that—how it’s always just almost time? It’s almost time for Harvey and Sam to get ready for work, only they can’t work in the rain, can they? It’s almost time for you and Wallace to get ready for school. It’s almost time for Tarabelle to go to work, and it’s almost time for me to leave, but not quite.” She laughed. “To tell the truth, Tan, I don’t know what time it is. It’s just morning and that’s enough.”

Mushy was talking in riddles, which made me wonder if she had spent the night drinking with Richard, and if they had gone out to Stillwaters. I scooted forward to escape the drops of rain that pelted me. Laura stirred, then yanked at the blanket I was dragging away from her. Mushy laughed again.

“I’m not going to school today,” I said.“I want to be here when you leave.”

“What’s Mama gon’ say?”

It was my turn to laugh. “Mama doesn’t care whether I go or not. She thinks I’m too old to go to school.”

Mushy was silent for a moment, then, in a dispirited voice, she said, “Tan, we need some light. I’m gon’ scream if I don’t get outta the dark. I can’t stand it. Listen to that rain. I used to like that sound, but I can’t stand it now. Rain and darkness. I need some light, Tan.”

There was a quiet desperation in her request that saddened me. I could not stop the rain, but I crawled over to the table and felt around, then with the flick of my wrist and the lift of a glass cylinder, I brought light into the darkness.

Tarabelle’s head rose from folded arms. “Go back to sleep,” she mumbled angrily.“What time is it anyway?”

“It ain’t no time, Tara,” I answered. “Mama broke the time last week, don’t you remember?”

“Silly,” she said, and pulled the blanket over her head.

Mushy covered her mouth and laughed. I slipped out of my wet gown and into a dress, then together we went out to the kitchen carrying the kerosene lamp.

While I pulled out pots and pans to place under leaks, Mushy made herself comfortable on the floor between Harvey and Sam. She was still wearing her red dress, but her makeup was gone, and she looked younger and more innocent than the night before.

&nb

sp; “Bring Judy in here,” she said.“She can’t move outta the rain by herself.”

With Judy and her basket in my arms, I returned to the kitchen to find Harvey up and building a fire in the stove, and Mushy in his spot between the blankets.

“When it rains in Cleveland,” she said, “I find myself somebody to sleep wit’. I don’t like being by myself.”

“We know that,” Sam teased.“Mushy, you’d talk to a rattlesnake if you thought he’d talk back.”

She ignored him.“There’s this boy in Cleveland wants to marry me. He been asking for two years, but I keep telling him to wait.”

“Now, Mushy, you know that’s a lie,” Sam said with a chuckle. “Ain’t no man gon’ chase after the same woman for two years.”

“His name is Curtis,” she went on.“He works at the hospital, too. I like him, but sometimes I feel like I want somebody different.”

“I know what you mean,” Harvey said.

“You tired of Carol Sue?” Sam asked.“She’s a pretty girl, but I can see how you’d get tired of her. She don’t want you to do nothing.”

“I ain’t tired of her,” Harvey said.“It’s her daddy that bothers me. Sometimes I wanna see her, but I don’t wanna go up to that house ’cause I know her daddy gon’ be there asking me what I’m gon’ do wit’ my life—like I’m s’pose to know—like I got some choices in this world.”

Mushy sat up. “Tell him to go to Hell.You ain’t courting him. You courting Carol Sue.”

“Same difference,” Sam said, and winked at Mushy.

“You know what,” Mushy said.“If I had twenty dollars to spare, I’d buy Sam some sense, and I’d buy you a backbone, Harvey.That ain’t to say you won’t stand up to a man, ’cause I know you will, but you let women run all over you.Take Mama for instance.You ain’t never been able to stand up to her.”

“What would you buy me, Mushy?”Wallace asked.

Mushy leaned across Sam’s outstretched form and kissed Wallace on the tip of his nose. “I wouldn’t buy you nothing, Wallace.You perfect just like you are. Maybe you can talk to these brothers of yours.”

The Darkest Child

The Darkest Child