- Home

- Delores Phillips

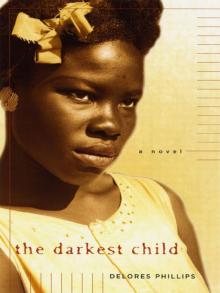

The Darkest Child Page 12

The Darkest Child Read online

Page 12

“They won’t listen to me.”

“Harvey, think about this,” Mushy said. “If Mr. Dobson didn’t want you seeing Carol Sue, then you wouldn’t be seeing her.All he gotta do is say the word, and she’d roll over and do whatever he say. That’s the kinda girl she always been.You marry Carol Sue and you gon’ screw on Tuesday nights wit’ the lights out, around the crotch of cotton bloomers, and you’ll know ain’t nothing else coming for a week.”

“Hell, that’d be a treat for Harvey,” Sam laughed.

“Mr. Dobson see something in you he likes,” Mushy rushed on. “It ain’t money and it ain’t smarts. Maybe he like yo’ looks and think you can make pretty grandchildren for ’im. Maybe he like that you already trained. Don’t get mad, Harvey, but you know what I mean.You already henpecked.You the type of man would bring yo’ money home and give it straight to Carol Sue.That’s all you know.”

Harvey wiped a hand across his forehead, leaving a thin line of coal dust on his skin.“They want me to come work at that funeral home,” he said.“That’s what her daddy wants, but Archie wants me to work wit’ him. He say the government making ’em build a new school for Negroes.He wants me to work wit’ him when it’s built. He says they’re gonna need two janitors, and he can get me on.”

“Nah, Harvey,” Mushy whined. “I want you to come to Cleveland. I want all y’all to come. I’m gon’ send for Tara first, then the rest of y’all. Archie Preston ain’t nothing but a cigar-smoking, pot-bellied, old fart. I know he s’pose to be yo’ daddy, but he ain’t never done nothing for you.”

“Mushy right. How you gon’ trust somebody who just walk up to you and say he yo’ daddy. Hell of a thang,” Sam said with amusement.“What else he been telling you.”

“Not much,” Harvey answered. “Every time I mention Mama, Archie gets this puckered look like he got something real sour in his mouth. He don’t never say nothing bad about her, he just don’t say much of nothing at all.”

“Screw him,” Mushy said.

“Yeah,” Harvey agreed half-heartedly. “He ain’t nobody. Ain’t got nothing to offer me, not even a name.”

“He offering you a job, boy,” Sam reminded him.

“Maybe,” Harvey said, “but I ain’t seen no school going up nowhere. Could be just talk.”

“No, it’s true,” I said.“Mr. Pace told our class that we’re getting a new school. They’re going to build it on that land behind the church.”

“Hambone mentioned something about it, too,” Sam said.“He said they either got to build one or let the Negroes go to school wit’ the whites.Wit’ a choice like that, what you think they gon’ do?”

“So that’s settled, ”Mushy said dejectedly.“Harvey gon’ spend his life in Pakersfield being a janitor, working wit’ his daddy and living wit’ his mama and trying to keep the two from meeting. Hell of a life if you ask me.”

“I don’t know what I’m gon’ do, Mushy,” Harvey said. “I don’t know that I can sit around here waiting for somebody to build a school.That might take a long time.”

“So you gon’ marry Carol Sue?” Sam asked.

“I don’t know what I’m gon’ do.”

The conversation died on that note, and Wallace rose from his pallet, stepped into a pair of blue jeans, and went out to the front hall.Tears sprang to my eyes.

Mushy sat up and pulled Judy’s basket closer to her, and I closed my eyes and visualized the routine of our household, one step ahead of reality.

In less than a minute, Wallace would return to the kitchen with the night bucket in his hand, Martha Jean following behind him. He would pick up the water bucket, and Martha Jean would open the back door.

“I know something about the midwife, ”Wallace baited. “Y’all wanna know?”

I opened my eyes and saw him standing there with the two buckets. No one took the bait, and I could not because I was on a higher plane, but low enough to sense we were missing something significant. I closed my eyes again.

Martha Jean would take the only two pots that were not collecting raindrops. She would wait for Wallace, then she would start grits in one pot and water for coffee in the other. After the coffee water was ready, she would warm a bottle for Judy.

My eyes and the back door opened simultaneously, and Wallace was back with the water. I closed my eyes again.

Where’s my coffee?

“Where’s my coffee?” Mama shouted from the comfort of her palace, and our day had officially begun.

Our mother’s presence in the kitchen had an unnerving effect on us. It sent my brothers out early into a pouring rain to loiter at the train depot where they would wait to say their farewells to Mushy. Tarabelle, before she left for work, sailed an urgent plea over Mama’s head to Mushy, to which Mushy nodded, ever so slightly, a promise.

“Put that baby down,” Mama said to Mushy over the rim of a chipped coffee cup.

The tension in the kitchen was smothering. Edna, Laura, and Martha Jean ate their grits in silence and with synchronized movements— spoon up, spoon down, chew, chew, swallow. I couldn’t eat.

The blankets had been rolled, and Mushy sat on one bundle with Judy’s basket at her feet. She kept fussing over the baby and would not meet Mama’s stare.

“You know that boy’s married,” Mama said flatly.“You ain’t got no business staying out all night wit’ no married man.”

Mushy said nothing.

“I heard you sneaking in here this morning. I didn’t raise my girls for people to be talking ’bout ’em. Ain’t you got no shame, Mushy?”

“Mama, I just wanted to sleep on a bed. I ain’t used to sleeping on the floor no more,” Mushy said.“It makes my shoulders hurt.”

“Humph,” Mama snorted.“So you just waltz into town and find yo’self somebody’s husband to sleep on?”

Mushy glared at Mama, then she balled her hands into fists and pressed them against the roll of blankets.“Richard Mackey is a big, dumb, slow-talking man that I ain’t got no need for. If I wanted him, he’d be packing a bag by now. But I don’t want him, so let’s just drop it, Mama.”

“He’s a handsome man wit’ a good job,” Mama said.“You just a slut, Mushy, and a cheap one at that.”

Mushy lowered her head, pressing her chin against her chest, then her eyes rolled upward and she said, “How you gon’ sit there trying to judge me when I’m the one person know just how lowdown and dirty you are? Don’t you dare talk to me about sleeping wit’ nobody’s husband.You know something, Mama? If you was anybody else, I’d get up from here and kick yo’ ass.”

Mama took another sip of coffee.“Pretend I’m somebody else,” she said as she tossed the remainder of the coffee at Mushy’s face.

On a crate, as far away from my mother as I could get, I saw the hot, brown liquid depart the cup, linger indecisively in midair, then accelerate in a lopsided flight. It landed in a soundless crash against Mushy’s startled face.

I rose to see if coffee had splashed on Judy, and Martha Jean moved frantically toward the basket, but Judy was safe.

Mushy gave a loud gasp, followed by a short scream, then she began to rub at her face with both hands. She rose from the blankets and stormed out of the kitchen, as Martha Jean and I followed.

Mushy snatched her coat from a nail, grabbed her suitcase from the floor, and fled our mother’s house with coffee dripping from her hair. I stood on the front porch beside Martha Jean and watched Mushy trudge up the muddy road with her suitcase banging against her leg.

From that moment, and for the next two days, we were forced to listen to our mother’s ambivalent sobs as she wept for a child she truly loved—and hated.

seventeen

In my daydreams, Plymouth School stands atop the highest mountain in Georgia. A paved road runs up one side, levels off in front of the school, then runs down the other side, past the football field, and on into oblivion. In reality, my mountain is just one in a series of small hills that, when combined, forms Plymouth.

“I’d like to pull her hair out by the roots,” Mattie said. “She’s having a party. That’s what they down there talking ’bout. They been whispering ’bout it all morning. I can’t stand her.”

In the section of bleachers across from us, Jeff Stallings sat with his elbows resting against the concrete behind him. He seemed to be studying the sky, or maybe lost in a daydream of his own.

“Mattie, what do you think of Jeff Stallings?” I asked, partly trying

to pull her attention from Edith, but mainly because I wanted to know.

“He just another nasty ol’ boy,” she answered. “I think he strange.”

“He’s smart,” I said in Jeff ’s defense.

“He strange.”

“Okay, but do you think he’s cute?”

“Boys ain’t never cute,” she said, glancing over at Jeff. “They s’pose to be called handsome, but I ain’t never seen no handsome one.”

“What about Harvey and Sam? All the girls think they’re cute— I mean—handsome.”

“They look like white boys,” she said, frowning at me. “That don’t mean they handsome. It just mean they got light skin.”

Laughter rose from the lower bleacher as Edith and her friends packed away the remains of their lunches. The boys on the field continued to run with their football, but other students were beginning to make their way back toward the doors of the school. “You like him?” Mattie asked.

I turned once more to glance at Jeff.“Yeah, I guess I like him,” I said.“He’s always real nice to me.”

“Too bad,” Mattie informed me.“He’s a senior, and he ain’t thinking ’bout you.” She reached down into her sock and pulled out a stolen stick of white chalk. On the concrete between our feet, she scribbled, TQ + JS.“This ’bout close as you gon’ get to him,” she said.

I was trying to erase the initials from the concrete with the sole of my shoe when Mattie nudged me. She glanced toward the aisle, and I turned in that direction to see Edith smiling down at me. I covered the scribble with my shoe.

“Tangy, I’m having a party on Saturday,” Edith said. “I’d like for you to come.You can stay overnight if you want.”

The heel of Mattie’s shoe pressed hard against my toe as she prompted me to refuse the invitation.“I’ll have to ask my mother, ”

I said.

“I’m sure she’ll let you come,” Edith said, “after all, we’re almost family. My mother says if your manners are anything like Harvey’s, you’re welcome at our house any time.”

Mattie sat still until Edith and her friends were out of the aisle and back in the schoolyard, then she bumped my shoulder roughly with her own.“Why didn’t you just tell her no?” she asked.

“Maybe I wanna go.”

“Well, go then.They gon’ pick at you.That’s the only reason she invited you.”

The bell rang, signaling the end of our lunch recess. I sat a moment longer, watching Jeff stand and stretch, then I joined Mattie for our walk back to class. I compared her appearance and my own to that of Edith and her friends. There was actually no comparison. Despite all the washing and scrubbing every Saturday, my blouse was dingy, and the single skirt and two dresses I owned always hung limp and wrinkled on my frame.

Mattie was no better. She had the one dress that would not hold a hem. No matter how often she repaired it, the thread always unraveled and the hem pouched at her knees.The strings in her shoes were broken and knotted into stubs, something I had not noticed before the invitation. She stood about three inches taller than I, and I figured she must have gotten her height from her father, along with the short, kinky hair that she never took a hot comb to.

“I’m not going to the party,” I said.

Mattie smiled.“I knew you wouldn’t go without me.”

I would have gone, though, because I liked Edith, regardless of how Mattie felt about her.

We entered the building through the main doors and moved swiftly across the lobby. It was a large area that served as an auditorium by placement of folding chairs, a gymnasium by removal of folding chairs, and a lunchroom when the weather kept us indoors. Opposite the main doors, at the far side of the lobby, was a small stage with a podium that stood against drawn wine-and-gold curtains. It was where I would stand to give my graduation speech— another one of my daydreams.

After school, I walked with Mattie until we reached her house on Cory Street in Plymouth. Usually, at this time of the afternoon, her mother would be in the side yard taking clothes from the lines, but today she wasn’t there. Mrs. Long was the smallest adult I had ever seen. She spent her days washing and ironing clothes, and eating Argo starch straight from the box. Her lips were perpetually white, and she had a lazy left eye as a result of too many beatings.Mr. Long had a reputation of being one of the meanest drunks in Pakersfield.

Mattie’s sister, Tina, was standing beside the steps when we entered their yard. She had a thumb shoved into her mouth, and stood with her head bowed. On the porch, Mattie’s younger brothers, Lobo and Bennie, were giggling and peering inside the house through a front window.

Tina removed her thumb and glanced up at Mattie. “We can’t go in,” she said.“Daddy’s at it again.”

“Drunk?” Mattie asked.

Tina shook her head and shoved her thumb back into her mouth. She was ten—too old to be sucking her thumb.

Mattie raced up the steps, shoved her bothers away from the window, and looked inside. She stood for a minute with her hands on her hips, then she kicked the front door several times, and yelled, “Dogs! Nothing but dogs!”

In Plymouth, the houses were set close to the ground and the porches were small.There were only four steps leading up to Mattie’s porch, and I stood at the bottom watching her. Her anger was unsettling and I felt awkward witnessing what amounted to a tantrum. Her hands struck the heads of her brothers in a series of loud slaps, then she grabbed them and roughly pulled them toward the steps.

“Sit here!” she barked. “Don’t go back to that goddamn window, or I’ll break yo’ arms.Y’all know better.” She hit them again until they were both holding their heads and crying.

When she stepped back into the yard, I found it difficult to look at her. “I’ve got to get on home, Mattie,” I said.

“I know,” she said, and her voice was calm, as if I had only imagined her rage a few seconds ago.“I’ll walk wit’ you as far as Duluth Street.”

As we began to walk, I stole a glance back at the house and saw Mattie’s little brothers sitting on the steps watching us, and Tina standing in the yard sucking her thumb. I wondered what Mattie had seen through the window, but I knew better than to ask.

“I ain’t going back to school next year,” she informed me as we reached the corner of her street and turned onto Lawson Street. “Daddy say I ain’t got to, but Mama want me to go. I’m sick of school.”

“What will you do if you quit?” I asked.

“I don’t know.” She shrugged her shoulders.“Get a job or something, I guess.”

“I don’t want you to quit, Mattie. I want us to graduate together.”

She laughed. “What make you think you gon’ graduate? I thought you said yo’ mama was gon’ make you quit.”

“I’ll find a way to go,” I said, and was surprised by the bitterness in my voice, and the anger I suddenly felt toward my best friend.

I made another comparison. I compared Mattie’s life to my own. She had obvious advantages, which included a smaller family, two parents, and a mother who encouraged her to attend school. The main advantage, though, was the beatings. In Mattie’s house they were fierce and frequent, but only bestowed upon

her mother.

“I can’t see where it makes no difference,” she said. “After you finish school, what you gon’ do? You’ll get a job doing the same thing somebody doing that ain’t never went to school. My daddy say a colored woman ain’t shit. He say they ain’t good for nothing. Can’t do nothing but stand around putting a whole lot of weight on a man.”

“We can teach,” I said. “And Mushy works in a hospital.There are things we can do, Mattie.”

“Mushy don’t work in no hospital in Pakersfield. I think my daddy right, so what’s the use going to school?”

I fell silent, thinking of the number of people who thought like Mattie. The first-grade classrooms, of which there were two, were filled to capacity every year, but by the time those students reached the seventh and eighth grades, their numbers had dwindled by nearly a third. Each year, the graduating class ranged between ten and twelve students out of the seventy or so who had begun first grade.

“. . . so I kicked her in her back,” Mattie was saying. “She was sitting there, too beat up and tired to cry, and it made me sick. So I went over and kicked her in the back. I was shame later, but sometimes I just get sick of it.”

“What are you talking about?” I asked. I was aware that Mattie had been speaking, but I hadn’t been listening to her. She had my undivided attention now.

She stopped walking and turned to face me, then she gave an irritable sigh before speaking again. “I’m talking ’bout my mama,

yo’mama, and my daddy. Mama all time saying how Daddy taking her money and giving it to yo’mama. Every time she get mad, she say mean things ’bout Miss Rosie.And every time, Daddy beats her up.Mama don’t know when to keep her mouth shut.”

“Did you say you kicked your mother?” I asked incredulously. “Mattie, you kicked your mother?”

“Yeah, I kicked her, and it wadn’t the first time. I told you I was sorry after I done it, but she makes me sick. If she gon’ say all them things to Daddy, she oughta be ready to fight, but she won’t even hit back.”

The Darkest Child

The Darkest Child