- Home

- Delores Phillips

The Darkest Child Page 28

The Darkest Child Read online

Page 28

Mama entered the room and leaned against the door frame. “You awright, girl?” she asked.

Tarabelle would not look at her, but she said, “Nah, Mama. I ain’t never gon’ be awright no mo’.”

“What’d them doctors say?”

“Say they wanna talk to you.”

“I ain’t got nothing to say to ’em, ”Mama muttered.

“That’s what I told ’em, ”Tarabelle said.“I told ’em you ain’t had nothing to say.”

“What you mean by that?” Mama asked.

Tarabelle did not answer. She whimpered and groaned, mimicking the melodramatics she had witnessed from our mother over the years.“Tan,” she said, “I don’t feel good. Spread me a blanket.”

I removed the blanket that covered her and spread it on the floor while Wallace helped her to her feet. Mama watched us.

“Is Tara gon’ die?” Edna asked, rising from the floor and staring at Mama.

Mama removed a few bugs from her face and arms, then she stepped completely into the room and slumped down on a chair. She sat staring at the coal stove for a long time, then she glanced at me and said, “Tangy Mae, you get yo’self cleaned up.You gotta go wit’ me tonight.”

For miles, against a narrow dirt road, cornfields and wheatfields raced through darkness, challenging a moon that knew nothing of their existence. It was a full moon that had risen for the sole purpose of watching over me.

Mama stopped the car in the yard of a two-story farmhouse. There were four other cars parked in the yard, and a skeleton of a car standing on cinderblocks beneath a willow tree. I had never been so far out in the country before, and could not say exactly where I was.Through an upstairs window, I could see a human shape pacing back and forth. The rest of the rooms upstairs were dark, and the light spilling into the yard came from the first floor.

“Tangy Mae, there’s a man in there that’s gonna help us get Sam outta jail,” Mama said. “He’s a lawyer named Ruggles. I want you to be nice to him, you hear?”

“What do you want me to do, Mama?” I asked, keeping my gaze fixed on the upstairs window. Anxiety was numbing my feet and legs.

“Do whatever he tells you to do. Be nice to him, and tomorrow I’m gon’ bring yo’ brother home.”

Did I care enough about Sam to risk my life as Tarabelle had done? Deep in my gut I knew this was the place that had nearly killed my sister, or at least it had started here, and I wanted no part of it. If there was a choice between saving Sam or myself, I would choose to save myself.

“I don’t wanna do this, Mama,” I pleaded.“I don’t wanna go in there.”

“Well, you going, and you gon’ do what he tells you to do.Don’t you start acting up and shame me out here, Tangy Mae. Now, you come on!”

She stepped from the car, and I tried to open the door on my side, but my hands were shaking too bad to lift the handle. Mama came around and opened the door for me, then she yanked me out by my hair. She did not understand that I was afraid. She thought she had taken care of my fear years ago. But it had slowly grown back.

“Let me have a look at you,” she said, fussing with my hair. She ran her hands along the shoulders of my coat, then glanced down at my legs.“You shouldna wore them socks, Tangy Mae, but it’s too late now.”

“Mama, please don’t make me go in there,” I begged, as she guided me across the yard.

She stopped abruptly, bunched the back of my coat with one hand, and began to roughly shake me. “You look here,” she said. “You gon’ do this, and I’m gon’ bring yo’ brother home so we can be a family again. If you don’t do it, Tangy Mae, I ain’t got no need for you. I’d just as soon chop you up in pieces and leave you out here in these weeds for the buzzards.”

I stifled my protest. She could kill me, leave me out here, and get away with it. She could get away with anything. People would probably think I had run off the way Mushy had done, and they wouldn’t even bother to search for me. I would lay in weeds until the buzzards plucked the flesh from my bones.

Moving as slowly as I dared, I followed my mother up five wooden steps and into a large kitchen where a frail, tired-looking woman sat at a table with an infant on her lap.

“Hey, Frances. How you doing?” Mama asked.

“Ain’t no need to complain, Rosie,” the woman replied. “This ’un yo’ daughter, too?”

Mama nodded.“Yeah.This here is Tangy Mae.”

“Y’all go on up. He in that last room on yo’ left.”

“I’m gon’ take her on up, then I’m gon’ come back down and have a cup of coffee wit’ you, Frances,” Mama said.

“This ain’t coffee I’m drinking,” the woman said and winked at Mama.

“Well, whatever it is, I’m gon’ have some, too,” Mama said, as she nudged me forward and up a flight of stairs.

There were five closed doors and an eerie silence along the corridor. Mama stopped and rapped on the last door on the left with her knuckles, then without invitation she opened it and shoved me forward.

“We here, Mr. Ruggles,” she said.

“I can see that, Rozelle. Close the door on your way out.”

Mama gave me a warning glance before backing from the room, and I was left with a stranger who sat on a chair and studied me with quiet amusement. When he smiled, he seemed harmless enough, but I clung to the spot where my mother had left me, and did not move a muscle.

“How old are you?” he asked.

My lips quivered and my mouth felt dry. “Fifteen,” I croaked. “I’m fifteen.”

He was a pale, middle-aged man with a torso and upper arms that sagged like foam sliding down the side of a beer mug. His dark hair, just beginning to gray at the temples, was oily and limp. He wore brown socks, white boxer shorts, and nothing else. He pressed his hands together and leaned forward on his chair.

“Get your things off,” he quietly demanded.

When I did not obey, his lips took on an unpleasant twist, and he rose from the chair.“Should I get Rozelle back in here to help you?” he asked.

“Please!” I begged.“Don’t do that.”

“Well,” he said, and nodded his head once, politely.

He returned to his chair and watched as I unbuttoned my dress and pulled it over my head.Tears—the silent kind—rolled down my face. I did not want this man to see my bra, or panties, or any of me, but he would not turn his head. My bra was too small, dingy from too much wear and washing, and the straps were held together by safety pins. I turned my back to him and heard him chuckle.

“Come here!” he ordered when I was standing naked before him.“Come sit over here.”

My reflection—a terrified little girl—crept slowly toward me from the windowpane behind his head. In the glass, the girl appeared skinny with mounds of flesh bulging from atop protective hands. I wanted her to disappear, but she just kept right on coming.

“Here. Sit here!”Mr. Ruggles said, patting one flabby thigh with his hand.

Awful, noisy, frightening sobs escaped my throat as he pulled me down onto his lap and closed his pale arms around me. He cradled me and wiped the tears from my face with the back of one finger.

“Don’t cry,” he soothed. “I’m not going to hurt you.”

I wanted to believe him, but the finger he had used to wipe my tears away began to pry between my hand and the breast it hid.

“Don’t fight against me,” he said impatiently.

But I did fight. Forgetting about my nakedness, I struggled against him until he dumped me to the floor and swung a sock-covered foot onto my belly to still me. His body shifted on the chair, and the chair gave a squeak, then he was on the floor beside me, his hands deep into my hair.

“Don’t make me hurt you,” he whispered against my ear. “Think about your brother. I can have him free by tomorrow.”

At that moment, I did not give one damn about my brother.Mr. Ruggles had straddled my chest, and I was concentrating on how to get his fat, flabby body off of me. I could not

buck him off, could not arch my back. My arms were pinned to the floor, and his heavy knees held them there. I was able to move my hands, and I flexed them until they connected with flesh, then I clawed.

He laughed. “If you scratch me one more time, I’ll break your little black neck,” he said, then gripped my hair like reins and snapped my head sharply forward.

I looked into his eyes and knew he meant it, and I did not want to die naked on a farmhouse floor. Harvey and Mr. Dobson would have to come for my body, and how could I ever explain to them? The sheriff and Chadlow would come and gape at me, and I would be unable to hide my nakedness. Damn!

The fight had left me, or at least Mr. Ruggles thought it had. He eased up from my chest to remove his shorts, and I quickly scampered across the floor. I had reached the bed and was nearly under it when he grabbed my ankle. I kicked with one leg, and he twisted the other. He dragged me from beneath the bed, let go of my leg and seized my hair again, then he sat on the bed and pulled my head up between his thighs. He was breathing hard from his exertion and I could smell his sweat.

“One bite, one scratch, and I’ll have Rozelle back in here,” he warned, then forced his rigid flesh against my closed, unyielding lips.

“Don’t!” I cried, struggling to turn my head. “Please, don’t do this to me.”

But he did, and I did not bite, and I did not scratch, because the grasp he had on my hair drew my face into a taut mass of pain.

When he was done with me, and I was being sick in a corner, he called my mother into the room. He faced her, and with fleshy hands pressed against a corpulent belly, he reneged on his promise to help my brother, citing my failure to satisfy him. I watched my mother plead with him until I was sick all over again. Finally, he granted her a second chance with the stipulation that I behave myself.

“It’ll have to be another night, Rozelle,” he said. “Look at her! What man in his right mind would touch her the way she is now?”

After we were home, and my mother had beat me for spoiling her plans, I went out to the back porch, and brushed my teeth and gargled with saltwater.

“What did you do?”Tarabelle asked, as I stretched on my pallet. “Why Mama so mad at you?”

“I threw up.”

“Oh,” she said.“They made you do it that way.You lucky.”

“I don’t feel lucky.Why didn’t you tell me, Tara?”

“I didn’t think you’d ever have to do it. Mama always said didn’t no man want you.”

“Can I get pregnant?” I asked.

“I think so,” she answered.“They do it to you all kinds of ways. I think all them ways can make a baby.”

“She says I’ll have to go back, Tara. I’ll have to go back until that lawyer gets Sam out of jail.”

We were silent for a long time, then Tara said, “You wouldn’t have to go if Mama was dead.”

“But she’s not dead, Tara.”

“Yeah. I guess it’s like Mushy said, ‘She ain’t never gon’ die.’”

forty - one

Night after night, I was taken from my home and delivered to one of the many beds at the farmhouse. One night when I was closed in a room with Harlell Nixon, I worked up the nerve to ask him about Sam. Harlell owned a barbershop, and people talked to him, told him all sorts of things. I asked him if he knew when the lawyer would get Sam out of jail.

Harlell laughed. “Girl, don’t yo’ mama tell you nothing? Sam doing a year for beating up that boy over in East Grove.That’s the way I hear it, and I ain’t never heard of no lawyer getting no nig-ger out when he doing time that a judge done gave him.They ain’t never really charged Sam wit’ killing Junior, but that don’t mean they won’t come back and do it later.”

“Is that why we need the lawyer?” I asked. “Just in case they charge Sam with Junior’s murder?”

Harlell laughed for the entire time it took him to undress. “Shit,” he said.“What lawyer anyway? I done tol’ yo’mama a hundred times, that motherfucka she giving her money to ain’t no damn lawyer.”

“What?” I asked incredulously. From the time Harlell pulled me onto the bed and until he finished with me, I asked that one question.“ What?”

Every part of my being had been stretched to the limits before my brother was finally released from jail. I had not seen Mr. Ruggles for more than a month, and I wondered what role he had played in the scheme of things—if any. My mother would not say, never mentioned his name.

It was May, and nothing growing on God’s green earth enticed or excited me. I felt I could have single-handedly ripped up the roots of the dogwood trees that blossomed on Fife Street. I allowed myself the privilege of anger, had no patience with my siblings, had even thought again of running away, and had made it as far as the four-lane highway before guilt pulled me back to Penyon Road.

I had suffered for Sam’s release, and now he came home. I tried not to be angry with him, but I couldn’t help it.When I looked at him, he reminded me of a centipede—a creepy, crawly, self-indulgent little thing. He stood in the front room close to the door, commanding our attention.The hair on his face nearly hid his lips, and there was a raised area on his head that looked raw and painful.

“I been cooped up a long time, Mama,” he said. “I need to stretch my legs.You got a couple of dollars I can hold ’til I get back to work? I’m thinking I oughta run up and see Harvey for a bit.”

“You ain’t been home fifteen minutes and already you talking ’bout leaving. I wanna have a look at yo’ head, and ain’t you got nothing to say to me?” Mama asked, as she gave him three dollars, which was probably all we had. “I don’t want you leaving outta here and getting in no mo’ trouble, Sam.You know they gon’ be watching you.”

“For every one eye they have watching me, I’m gon’ have two watching them. I ain’t never going back to jail, Mama. I just need to be outside for a bit. See things again.We’ll talk when I get back. We can talk all night if you want.”

Mama chuckled. “Yeah, I guess you do need to stretch them legs.You moving so much look like you gon’ break out and dance in a minute.”

“Harvey ain’t home, ”Wallace said. “He getting Miss Julia ready for her funeral.”

“Miss Julia done died?” Sam asked.

“It ain’t bad she died,” Tarabelle said. “She was in real poor shape. She looked ’bout bad as you do.You sho’ you ain’t sick or something, Sam?”

Sam laughed.“Tarabelle, girl, you ain’t changed a bit.Ain’t nothing wrong wit’ me.”

“You could stand a shave,” Mama remarked, “and before you leave outta here, I wanna know who did that to yo’ head.”

“I love you, Mama, and that’s all that matters,” Sam said, as he moved toward the front door. “Don’t matter who did nothing to my head.”

Mama grabbed his arm, then she studied his face long and hard as if to convince herself that this was the same child who had been taken away from her at the end of last summer. “Is it over, Sam?” she asked soberly. “Are they gonna come back later and say you killed Junior?”

He leaned down and kissed her cheek.“As far as I’m concerned, Mama, it’s over.”

I followed him to the door and out onto the porch, and I could see Hambone’s car waiting on the road. I wanted to yell, “Sam, you’ve been in jail for nine months. Stand still for a minute! Talk to me!” Maybe I said it aloud; I don’t know, but Sam stopped and turned to face me.He took my hand and led me down to the yard.

“Tangy Mae, I heard some things while I was in that jail,” he said. “A few people tol’ me some awful stuff ’bout you. I wasn’t gon’ ask you ’bout it ’cause I didn’t wanna believe it, but the way you been looking at me ever since I walked through that door, I know it’s true. I’m sorry, and that’s all I know to say.”

I began to cry, and Sam squeezed my hand.

“You go on and cry, Tangy Mae,” he said.“You got a reason to cry.When I get time, I’m gon’ cry, too.”

“How did they treat you

in that jail, Sam?”

“Probably better than you been treated. It’s hard when somebody take yo’ freedom from you, but the sheriff and his deputies was okay. The sheriff in Caloona was awright, too. But Chadlow was something else. Sometimes he’d pull up a chair when wasn’t nobody else around, and he’d talk to me through them bars.Tell me how I was gon’ fry in the electric chair for what I done to Junior. He would always suppose—Nah, ‘imagine, ’ that was the word he used. He’d say, ‘I imagine Junior musta squealed like a little girl when you killed him, boy.’ Or he’d say, ‘I imagine it musta took a dozen of you dumb niggers to figure out how to get that rope around that boy’s neck.’ One day he stuck a broom handle in my cell, started poking and prodding me wit’ that thing. I grabbed it and tried to pull him through them bars. Scraped my hands up real good.” He opened both hands so I could see his palms.

“I’m sorry, Sam.”

“Uh-uh.Nah.You ain’t got nothing to be sorry ’bout. I’m the one that’s sorry. I’m sorry you had to go through all that stuff you been through. I didn’t wish nothing like that on you, Tangy Mae, but when you locked up in jail, you ain’t got no control over nothing. And I ain’t never had no control over Mama, anyway. I was upset wit’ her when I heard, but I knew she was just doing the best she knew how to get me outta that mess I had done got myself into.”

I nodded. “I’ll be okay, Sam. How about you? How are you doing?”

He shook his head and smiled.“Tangy Mae, I feel like if somebody took mad away from me, I’d be walking ’round empty. I’m gon’ tell you what I don’t ever want Mama to know. Chadlow let them Griggses in that jail on me—the daddy and all three of them boys.They beat me real good.They didn’t kill me, but they shoulda, though.”

I watched as he ran down the bank and climbed into Hambone’s car, then I returned to the front room where my mother sat with her head resting against the back of her chair. She was happier than she had been in a long time.

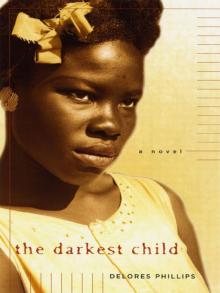

The Darkest Child

The Darkest Child