- Home

- Delores Phillips

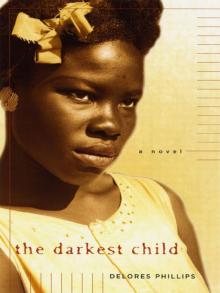

The Darkest Child Page 29

The Darkest Child Read online

Page 29

“I’m going up to the flats to see Tannus,” she said. “I gotta let him know that Sam is free. I gon’ let him know that my baby didn’t kill his boy.”

“Don’t do that, Mama,” I said. “Mr.Tannus already knows that Sam didn’t kill Junior. If you start talking, you’ll just get the rumors started again. Some people think Sam is getting away with murder.”

“Who saying that?”

“A few people who don’t know how close Sam and Junior were.”

“Well, I’m gon’ put a stop to it,” she said.

She brushed past me, raced down the steps and out into the field. As she drove away, I knew, and thought she should have known, that she would not be able to stop the rumors. She couldn’t stop them about Sam, she couldn’t stop them about herself, and once they had gotten started about me, she wouldn’t be able to stop those, either.

I followed the trail of dust left behind by my mother’s car until I reached the paved surface of Fife Street, then I turned right and headed toward the flats.When I arrived on Motten Street, Martha Jean was sitting on the porch swing, looking as though she would explode from the weight of her unborn child. She watched my approach, and smiled slightly when I joined her.

“Velman where?” I signed.

She did not answer, but took my hand and placed it against her abdomen. I allowed my hand to linger for a moment, then repeated my question.“Velman where?”

“He’s back up in there somewhere,” Skeeter said from behind the screen door. He stepped out onto the porch.“Time for me to get to work. Pretty good the way this thing works out, with Velman getting in before I have to leave. That way Martha Jean is never alone. Don’t want her to be by herself when that baby comes.”

Skeeter was the same height as Velman, but he was heavier, and about a shade lighter in complexion. He was a handsome man. His eyes reminded me of Velman’s. They were small and clear, and right now they were laughing.

“I never would’ve thought that tiny little girl that Velman brought home would ever get so fat,” he teased, and leaned down to tap Martha Jean’s protruding navel with his finger tip.

“Baby,” Martha Jean signed.“Velman say, fat. See feet, no.”

Skeeter laughed, then said, “He right, too, ’cause you sho’nuff done got fat.”

“Ain’t nothing funny about no fat woman, Skeeter, ”Velman said lightheartedly as he stepped out onto the porch. He was wearing trousers, but no shirt or shoes, and Martha Jean sent him back inside to dress.

“Well, I’ll see y’all later,” Skeeter said.“Take care of my girl ’til I get back.”

We watched him swagger up the sidewalk, then Martha Jean pulled herself to her feet, and I followed her inside.Velman was sitting on a chair in the front room, pulling on a pair of socks.

“Little sister, how you say jealous with your fingers?” he asked. “I wanna tell my wife to stop being so jealous.”

“I don’t know,” I answered. “I’ve never had to use that word.”

“Martha Jean’s even jealous about Skeeter,” Velman said. “It don’t make no sense the way her and Miss Shirley be going at it. That woman trying to like my uncle but my wife don’t want her over here. Skeeter thinks it’s funny, but Miss Shirley don’t think it’s funny one bit.”

I shrugged and sat on the floor beside the coffee table. Martha Jean entered the kitchen.

“She’s probably gon’ eat something else, ”Velman said.“I thought Miss Rosie was making fun back when she first said Martha Jean was gon’ have a baby. How she know that, you reckon? I hadn’t seen no difference in her back then, but I took her on over to Dr. Mathis, and that’s what he said, too. It scares me, little sister. I don’t know if I’m ready for it.”

“You’re ready,” I said. “There’s nothing you can do about it now.”

“Yeah, you right,” he said, rubbing at a worry line in his forehead. “Hambone was by here again last week.Talking.Always talking. Got me thinking I’m supposed to mad at somebody, and I don’t even know who.”

“Sam’s out,” I said.“You can tell Martha Jean. It’ll probably make her happy.”

He nodded, settled against the chair cushion, and closed his eyes. “Everything makes her happy,” he said.“Sometimes she be moving them fingers all happy-like, and I don’t know what the heck she be saying. I got a lot to learn before I can keep up with what she say, but I figure we got all our lives. I be looking at her lately, and wondering if our baby gon’ be able to hear.”

Velman was so preoccupied with Martha Jean that I was sure he had not heard my news. I repeated it.“Sam came home today. He’s out of jail.”

“Hey, that’s great,” he said, opening one eye to look at me.“So the sheriff finally listened to reason?”

Velman had opened the door for me to unburden myself, which was what I needed to do, but before I could say anything, Martha Jean waddled in from the kitchen, popping the last of a biscuit into her mouth. She settled on Velman’s lap as if that was the only place in the room to sit, and he shifted on the chair and supported her back with his arm. He flicked his tongue and stole a crumb from the corner of her mouth, and she buried her face against his neck while he stroked her abdomen. It was an intimacy that negated all existence beyond that chair, and I felt an intruder.

I fought a compelling desire to snatch my sister from the arms I craved comfort from myself. I did not merely want her man; I needed him. He could be my deliverance, rescue me from Penyon Road, mend the broken pieces of my heart and make me whole again.With as much dignity as I could muster, I rose from the floor and went toward the front door, needing to get away from this house and all the things I could not have.

“Where you going, little sister?”Velman asked.

“Home.”

“What’s the rush? Stay for supper.”

My hand was on the door, and all I had to do was keep walking, but I turned around.

“I’m going home,” I said bitterly, unable to control my hurt and anger any longer. “Martha Jean can stay for supper. She’s bought and paid for. Nobody traded anything for me, and I’m going home.”

Rage propelled him across the room. He gripped my shoulders and glared down at me. “Don’t you ever say anything like that to me again.”

For long agonizing seconds, I could not speak, then my voice eased around the lump in my throat. “I’m sorry,” I said. “I didn’t mean that.” But my mind screamed, Why didn’t you choose me?

He removed his hands from my shoulders, and composed himself.“ What’s going on?” he asked.

It was getting late, and I stared out the screen at children playing in shadows along the sidewalk.“Mama used me to get Sam out of jail,” I said quietly. “I’m scared, Velman. I’m so scared.”

“What do you mean, she used you to get Sam out?”

Settling myself on the couch, I stared up at Velman, then beginning with Mr. Ruggles, I told my story.As I spoke, I could see it all as clearly as though I were suspended above a bed at the farmhouse. The terrified girl in the room was someone else. Not me. She floated like an impotent ghost. She lay on one bed with a tall man who smelled of garlic. She bowed at another bed for Chadlow, her feet on the floor, her arms pressed against the mattress. She was just a child, really, who collapsed from pain, only to be hoisted up by her mother. Night after night the men came, and the gentle ones were the worst, for they assumed they could coax life into a girl who died each night before they even touched her.

“Damn, ”Velman whispered when I was done.

“What?” Martha Jean asked. She had come to sit beside me, and her fingers steadily repeated that one word.“What? What?”

“Hurt,” I signed.

Velman paced the room, then he stepped toward the couch and I waited for him to say something. His mouth opened and closed. I saw him lift a foot, and the coffee table flew across the room and struck the wall. He followed after the table, kicked it again, then slammed his fist against the wall just above a framed sti

ll life of red roses. The roses sprang from their hook and crashed against the overturned table. Martha Jean stared in alarm, but I sat back and watched the destruction. It was futile, yet I understood it was for the love of me.

forty - two

We were awakened in the middle of the night by the smell of smoke and the peal of sirens some distance off in the heart of our city. It was an uncommon sound in Pakersfield, which made it frightening and exciting at the same time. We lit the kerosene lamps and filed out into the night.

“Where’s Sam?” Mama asked, a hint of panic in her voice.

“He never came home, ”Wallace told her.

Mama swore, and her words drifted up into the smoke-filled air. We stared toward the east where I expected to see flames leaping for the sky, but whatever was burning was too far away or too low for us to see.

Miss Pearl arrived early the following morning to tell us that she and Mr. Frank had attempted to go to work and had been rerouted by the police.“Frank went on around through Plymouth, but I told him to let me out,” she said.“They say somebody done tried to burn down everything on Market Street.They got barricades up and they ain’t letting no coloreds into town. Say they ain’t stopping nobody from going to work, just gotta find another way to get there.”

“I gotta go to work, Mama, ”Tarabelle said.“Miss Arlisa gon’ get rid of me if I keep staying off.”

Mama nodded.“You ain’t gotta go through town to get to East Grove.You go on.”

“We don’t have to go through town to get to school, either, Mama,” I said.

She rested her elbows against the tabletop and cupped her hands around her chin. She had a faraway look, like she was staring through me and could see something no one else in the room could see. Finally, she said, “If school that important to you, Tangy Mae, you go on. For all you know, yo’ brother could be burned up in a fire, and you standing there talking to me ’bout school.”

Tarabelle left almost immediately, but I allowed guilt and indecisiveness to slow me down, which is how I happened to be in the kitchen when Angus Betts and Chadlow stormed into the house. Miss Pearl shrieked, but Mama sat silent, staring with indifference at the gun Chadlow aimed at her chest.

The sheriff was also holding a gun, but his was pointed toward the floor. He glanced about the room, then asked, “Where is he, Rozelle?”

“I ain’t seen him, ”Mama answered.“He didn’t come home last night.”

“You’d better not be lying to me,” the sheriff said, raising his gun slightly. “I’ve got Marcus and Beck searching those woods out there. If we find him hiding out back there or anywhere near this house, I’m taking you in, too.”

“I’m telling you, Angus, I ain’t seen him since yesterday.”

The sheriff raised his gun and pointed it at her head.“What did you call me?” he asked.

Mama seemed confused. She placed one trembling hand to her throat and stared at him. “What’d I say, Sheriff?” she asked innocently.

He lowered the gun and turned to Chadlow.“You keep an eye on them while I search the rest of the house.”

The minute the sheriff was out of the room, Chadlow stepped closer to Mama and said, “He burned down my place of business, Rozelle.That means if we don’t catch him, you’re gonna owe me. Do you know how I deal with people who cross me?”

My mother trembled with fear. It was the kind of fear she despised, the same kind she had burned from my flesh. Chadlow stared down at her, and she closed her eyes as tight as she could.

There was not much to search in our house, and the sheriff was back in less than five minutes. He holstered his weapon and stared at my mother with contempt. “Rozelle, I don’t know where that boy is, but I’ll get him.When I find him, I’ll make him wish he’d never been born. And don’t try to tell me that it wasn’t him. He drove through this town throwing Molotov cocktails. Do you know how much damage that can do?”

Mama shook her head.“I don’t know what that is.”

The sheriff looked at Wallace. “Do you know anything about this?” he asked.

“No, sir, ”Wallace answered quickly.

“I’ve got a good mind to just go on and arrest everybody,” the sheriff said.“I’m ruined in this town. I stood up for that boy, asked the judge to set him free, to consider he was injured while in my care. I see now that I shouldn’t have done that.The Griggs’s furniture store is gone.” He flicked his fingers. “Just gone.The Pioneer Cab Company is rubble, Chad’s café was destroyed, and businesses all along Market Street were damaged.The fire started at Griggs’s and spread from there. I can’t even describe the mess they made on the courthouse lawn or what they did to the water fountain. Ralph was working late at the depot, and he says he saw your boy and some others just before the fires broke out.”

Mama wept softly into a dishcloth that Miss Pearl had handed her. She made no effort to deny anything the sheriff had said.

The sheriff watched her for a moment, then he turned to Chadlow and said, “Let’s get out of here.”

Once they were gone, Mama scraped a mess of bugs from her cheek. Her fingernails left three red marks running from below her right eye down to her chin, and I knew I was not going to school.

“I’m gon’ see if they all left, ”Wallace said, rising from his milk crate.

I followed him out back where we stood on the porch and studied the path between the trees for some sign of movement.There was nothing.Wallace went down the steps and mounted his bike.

“I’m gon’ find out what happened,” he said.

“Wallace, don’t go near town,” I said.

“I won’t. I’m going up on Plymouth and down to the flats. Somebody knows something, Tan.”

I stepped down from the porch, and walked slowly toward the woods.The sheriff ’s men had invaded my forest, trampled through the underbrush, and disturbed its tranquility. I could feel their intrusion, although they were long gone. I walked in circles, thinking of the price I had paid for Sam’s freedom, thinking of Mr. Pace and his plans for my future, thinking of my mother and her bugs.

When I returned to the house, Harvey was on our front porch talking with Mama and Miss Pearl. Mama had stopped crying and was concentrating on the information that Harvey was apprehensively imparting. I eased down on a step to listen.

“I’m telling you, he ain’t nowhere in town, Mama,” Harvey said. “I been everywhere.The sheriff ain’t lying to you. He came up to the house this morning wit’ Chadlow, and they searched the whole place.They even searched the funeral home.Ain’t nobody seen Sam. It was him and Hambone, Maxwell and Becky.They all gone.”

“That don’t mean Sam burned nothing down,” Mama said. “People all time blaming things on Sam.”

“He did it, Mama. Sam was in jail a long time. Every day he probably got a little madder, and he had time to plan this. I’d say Hambone knew about it, too. If Sam didn’t do it, where is he? How come he ain’t came home? He been outta jail for one day, and all of a sudden half of town burns down.Who ain’t gon’ think it was him?”

“You know, he got a point there, Rosie,” Miss Pearl said.

“Go home, Pearl!” Mama shouted. “You too, Harvey. I don’t need nobody ’round me that’s against Sam.Y’all don’t know that he did nothing.”

Miss Pearl rose from her chair. “I’m going,” she said. “I didn’t believe the sheriff when he was saying Sam killed Junior Fess, but looks like to me he got the right somebody this time.”

“He ain’t got him yet,” Mama retorted.

“Nah, Mama, but they gon’ have him soon,” Harvey said. “It’s just a matter of time.” He started down the steps, then stopped and stared out toward the road where Wallace was pedaling for home with all his might. “Look at Wallace. He got some news. Maybe they done caught Sam.”

Wallace leapt from his bike and let it fall to the road. He scurried up the embankment. “Miss Pearl!” he called excitedly. “Miss Pearl! Martha Jean done had a baby.Velman needs you to ge

t over there right now. He don’t know what to do. Hurry up, Miss Pearl!”

“Lord have mercy. Who caught it?” Miss Pearl asked as she reached the ground.

“Huh?”

“Who caught the baby? Who delivered it?”

“Velman, I guess, ”Wallace answered. “Ain’t nobody there ’cept Velman and Skeeter. Skeeter went to get Miss Shirley, but she too upset ’bout Max and Becky to be bothered.”

“Come on, Rosie,” Miss Pearl said. “Run me over there right quick, see ’bout this child.”

“I ain’t going nowhere,” Mama said.“I gotta wait for Sam.”

“I’ll drive you,” Harvey offered.

“I’m going, too, ”Wallace said.

“Me, too,” I said, and started for Mr. Dobson’s car.

“Tangy Mae, you ain’t going nowhere, ”Mama called down from the porch.“What if I have to run someplace to see ’bout Sam? You gotta be here wit’ the girls.”

“Get my bike out the road, Tan, ”Wallace said as he climbed into the car.

“Wallace, what did she have?” I asked. “What did Martha Jean have?”

“A girl.”

The car pulled off, and I went down to the road to get the bike, then I went to the back porch to pout in private and to plot a diversion that would get me to Motten Street.

forty - three

They did not wait until the wee hours of the morning to retaliate. The first fire broke out on Tuesday evening long before midnight, but we did not stand gazing into darkness as we had done before.These flames were visible, too high, and too close.

We joined a distressed throng on Canyon Street where hoses had been strung from the two closest houses.We raced back and forth with anything that would hold water, filling our vessels from a faucet in Walter Vanna’s yard.We did all we could in a futile attempt to save Logan’s store, then stood back and watched as the fire consumed it.

When there was nothing more to do, we began to disperse, then somebody yelled, “Oh, my God! Look!”

The Darkest Child

The Darkest Child